The village of Pentlow sits on the Essex side of the Suffolk-Essex border. When I visited its 12th century round-towered church this August, I didn’t know I’d find so many tragic personal stories in its tiny churchyard.

It was a gorgeously warm day in the last week of August. I had stayed in on the Suffolk side of the border in Cavendish overnight and decided to walk to the church of St. Gregory and St. George in Pentlow. My route finder said it would be about a 15 minute walk, not accounting for the multiple times I would undoubtedly stop and take photographs along the way. Little did I know, I would be passing by some places that would feature heavily in the stories I’m about to tell.

I started at the village green in Cavendish, turning right at the junction of the Pentlow road. It is here, while passing over the Pentlow Bridge, that you cross the county border in to Essex. This has been a crossing point on the River Stour at least since the 17th century, when a bridge is shown here on Speede’s map of 1610. Today, it has a raised walkway alongside the road, to allow foot traffic to pass in times of flood. Looking to the right you see the stunning Pentlow Mill, which sits on the banks of the Stour, framed by weeping willow. It is every bit how you would imagine a country scene, worthy of painter Thomas Gainsborough, who lived in nearby Sudbury.

It is only a short walk to Pentlow church, hidden behind its avenue of trees. Whenever I step into a churchyard or cemetery for the first time I am always, for a moment, struck by the weight of history in these places. Every headstone represents a life with a biography waiting to be written, if we only knew the trials and tribulations of their life and loves. Most will be stories never told, but just a few left enough clues to their lives in records and newspapers to be memorialized by strangers they’ll never meet.

I had purpose in visiting this little churchyard: not only because it is one of only six round-towered churches in Essex, but because I wanted to find the grave of a Home Guard member who had been killed in 1944. In this article I’m going to tell the story of his accident, but also that of a girl murdered by her lover who was buried here, a young Royal Marine of the village who is remembered on a plaque inside the church, and a sea captain who disappeared in the South China Seas.

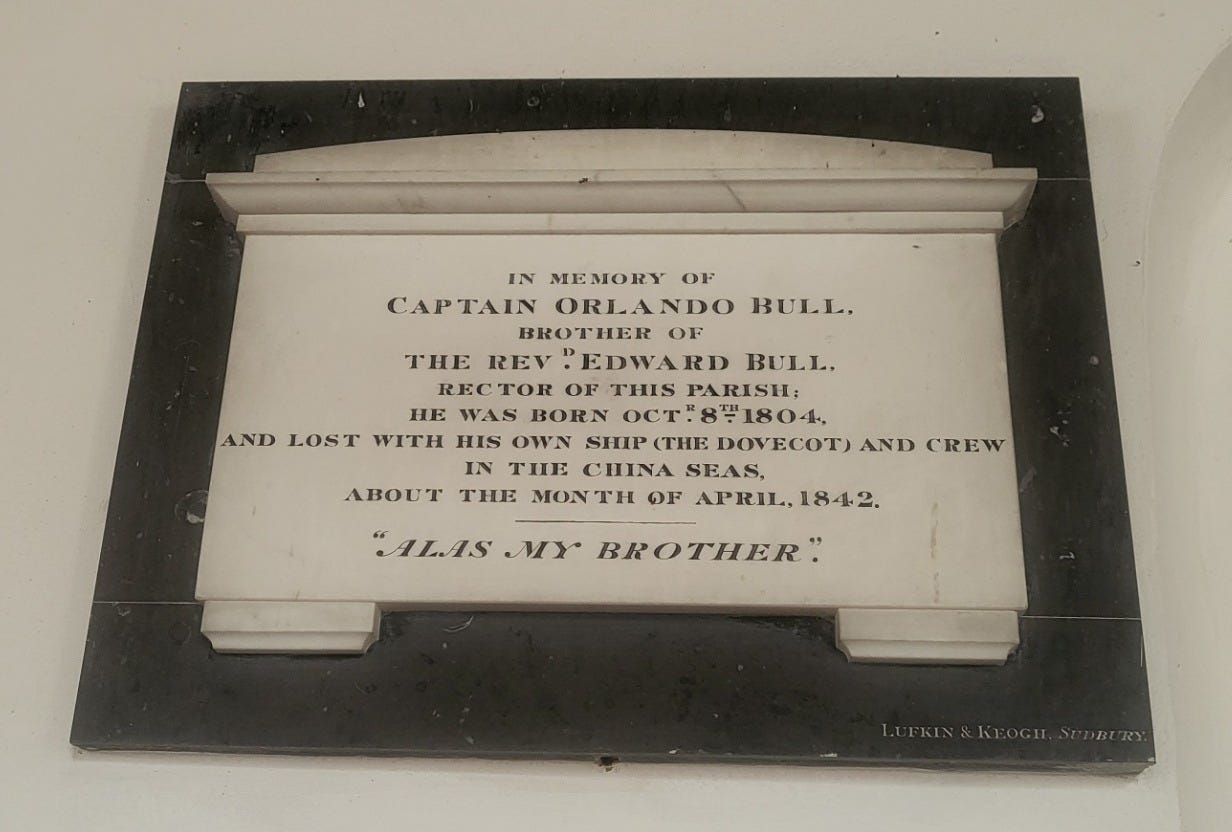

I will start with the oldest of the memorials I took an interest in. High up on the wall of the church was a plaque which reads:

In memory of

CAPTAIN ORLANDO BULL

BROTHER OF

THE REVd EDWARD BULL

RECTOR OF THIS PARISH

HE WAS BORN OCT 8TH 1804

AND LOST WITH HIS OWN SHIP (THE DOVECOT) AND CREW

IN THE CHINA SEAS

ABOUT THE MONTH OF APRIL 1842

-

“ALAS MY BROTHER”

The Dovecot was on voyage from London to China when it disappeared. The brig was sighted on the Straits of Gaspar, but vanished soon after. On Saturday 26th November (1842) the English Chronicle reported under the heading SHIPPING INTELLIGENCE : ‘An English vessel, supposed to be the Dovecot, is reported wrecked at Hainan in April last; cargo plundered and crew supposed to have been murdered.’

The Dovecot was indeed wrecked on Hainan, an island in the South China Sea on or around the 16th April. Speculation was that the crew had been murdered by Chinese pirates who plagued those waters at the time, though word from China put the blame at the door of the island natives for the demise of the crew.

Captain Bull had been born Orlando Sadler Bull, in Pentlow in 1804 to the Reverend John Bull and his wife Margaret. He was one of ten children to the couple. His brother, the Reverend Edward Bull, who placed this plaque in the church, also built the Pentlow Tower in the rectory grounds. The tower, which is now Grade II listed, was built in 1859 in memory of his parents. The loss of Captain Bull seems like a tragic way for a family to lose a loved one. Never quite sure of their demise; having no grave to visit to remember them. The plaque at least allows for some remembrance.

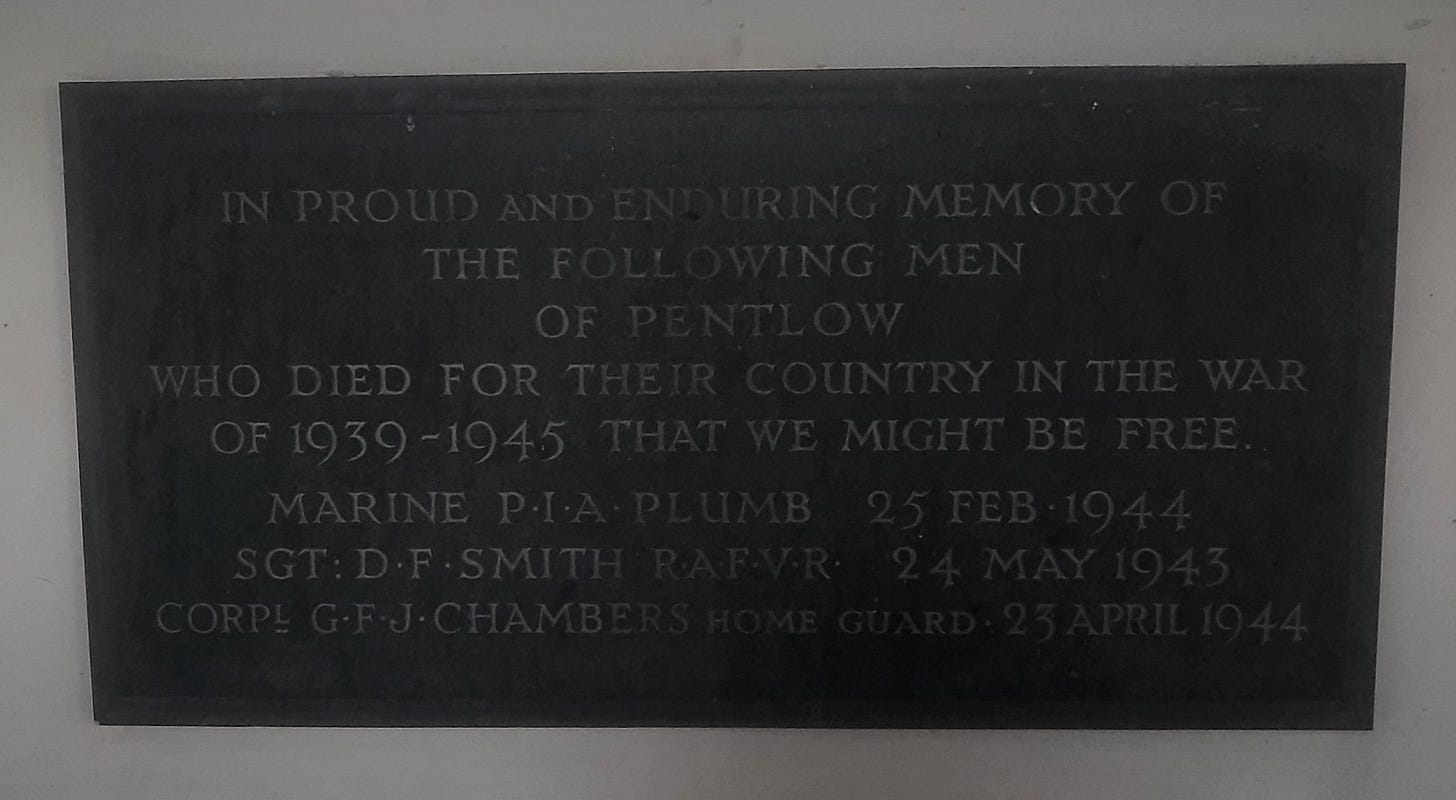

Captain Bull is not the only untimely loss at sea memorialised in Pentlow church. On another plaque in the church an inscription reads:

IN PROUD AND ENDURING MEMORY OF

THE FOLLOWING MEN

OF PENTLOW

WHO DIED FOR THEIR COUNTRY IN THE WAR

OF 1939 – 1945 THAT WE MIGHT BE FREE

MARINE P.I.A.PLUMB 25 FEB 1944

SGT D. F. SMITH R.A.F.V.R 24 MAY 1943

CORPL G. F. J. CHAMBERS HOME GUARD 23 APRIL 1944

Philip Ian Arthur Plumb had been born in Pentlow to Joseph and Lily Plumb on 3rd April 1924. When he turned 18 the Second World War was already several years in, and he chose to join the Royal Marines. At this young age he also married his sweetheart, Gwendoline. I can’t find a record of the incident that led to his death, but on 3rd of January 1944 he lost his life in the water, aged just 19. He was assigned to HMLCF 37 at the time, an operational landing craft used to deploy Royal Marines into combat zones. He was found drowned, his body washing up at Hythe Pier, Southampton. Given the location where he was discovered he was perhaps based at Portsmouth, on training exercises in preparation for Operation Overlord which would take place six months later. While the plaque in the church states his death being 25th February 1944, his headstone and all other references to his death state that he died on 3rd January 1944. He is buried in the neighbouring village of Belchamp St. Paul, where he is remembered with a Commonwealth War Grave Commission headstone.

The second man on that plaque was an air gunner with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Sergeant Donald Fred Smith was just 22 years old when he lost his life in a training accident in Nottinghamshire. On the night of the 23rd/24th May 1943 his crew took off in their Lancaster bomber from RAF Wigsley. The night training flight was intended to allow flight crews practice navigating and locating targets over a designated city, and the ground units practice using their defence equipment on the ground. It was around 0300hrs when Lancaster W4303 came within range of their target town and was illuminated by a number of searchlights. To avoid friendly-fire incidents, an aircraft of a training run would usually drop a coloured recognition flare at this point to prevent anti-aircraft guns being fired. For unknown reasons on this occasion the flare was dropped only after severe evasion manoeuvres had been taken by the pilot. The plane was not shot down, but the violent evasive action caused the tail fins to fail and in turn the break-up, mid-air, of the aircraft. The aircraft came down just outside the village of Humbleton at 0308hrs. All eight of her crew were killed, including Air Gunner Smith. He was returned to his home village of Pentlow and is buried in the church.

The last name on that memorial plaque to the dead of the Second World War, Corporal Chambers, was the chap who had brought me to this place.

On 23rd April, 1944 members of the Home Guard – 15th Essex Battalion, were attending a training exercise at Rectory Farm in Gestingthorpe. Captain Philp was giving a demonstration on how to deal with unexploded grenades. The Captain was the battalion weapons officer and was experienced in handling explosives. During the demonstration it is thought that some unstable gelignite detonated, perhaps due to the heat of the day, as there was a report of it being sat in direct sunlight at the time. At the inquest it was stated that Captain Philip had shown all due precaution with regard to the grenades he was demonstrating and had impressed upon the men watching that safety precautions needed to be observed. Sadly the accident claimed six lives, and three other men were injured but survived.

Those lost were:

Corporal George F. J. Chambers – Age 29 – Buried in Pentlow

Corporal John B. Partridge – Age 36 – Buried in Belchamp Walter

Captain John Scantlebury Philp – Age 43 - Buried in Castle Hedingham cemetery

Sergeant John W Cousins – Age 33 – Buried in Sible Hedingham churchyard

Sergeant Thomas A Firman – Age 45 – Buried in Sible Hedingham churchyard

Corporal Cyril A Halls – Age 32 – Buried in Sible Hedingham churchyard

The three men buried at Sible Hedingham lay next to one another.

The final Pentlow story I want to tell is that of Nora Plumb, a girl who was buried in the churchyard in 1929. If her grave is marked, I couldn’t find it. He mother was a widow and partially supported by Nora, so I’m not sure she would have even been able to afford to have a headstone made. Nevertheless, she is here somewhere.

On my walk from Cavendish to Penlow I had passed by The Bull public house. Now closed to trade and at the time of writing (Summer 2024) up for sale; a beautifully historic old inn on the main road through the village. It was here in September 1929 that a horrific murder was discovered. It became the scene of a love affair that went horribly wrong when a jealous lover took the life of a young woman, before ending his own life.

The Newmarket Journal reported:

MURDER AND SUICIDE VERDICT RETURNED AT INQUEST

‘Living at the Bull Hotel were Mr and Mrs Richardson, their daughter and their servant, Nora Plumb. Nora was about 25 years of age and had been with the family since she left school’

The article goes on to describe the events of that night and the evidence brought up at inquest.

-

Customer and frequent visitor was George Morley, a 37 year old gamekeeper out of Great Thurlow. During the First World War George had a very creditable war record and served in the Suffolk Regiment, rising to the rank of company Sergeant Major. He was wounded on three occasions, each time returning to the front. He was discharged at the end of the war, but soon re-enlisted, this time as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corp. He left the army in 1928 and went back to the occupation he had had before joining up, that of gamekeeper.

It is said that he and Miss Plumb became friendly and he made it known that he wanted to marry her. Those that were able to speak on the subject had differing takes on their situation. It seems that those known to George were under the impression the couple were engaged and that he was preparing a home for the couple. He had expressed an interest in having a wedding before shooting season started. Those that knew Nora were aware that he had proposed marriage, but all said she had given no answer.

On Thursday 5th, the day that this crime took place, George arrived at The Bull to visit Nora. It was heard at the inquest that he arrived in the morning, but seemed to hang around all day, appearing to want to keep an eye on her. He asked to see her again in the evening, and when the pub closed at 10pm she went to the kitchen to speak with him. The landlord, his family, and some guests stayed chatting in the front room of the pub. About 45 minutes later the landlord and his guests heard what they described as a ‘pop’, and soon after, another. Thinking it was perhaps a bottle that had blown a cork he went to investigate in the bar. Finding nothing amiss he went through to the kitchen. It was here he discovered Nora, laying on the kitchen floor, with horrific injuries to her face. The Newmarket Journal described the scene ‘a terrible sight met his gaze. Stretched out on the floor in a large pool of blood was Nora Plumb, with her face shockingly disfigured.’

The village police house was situated just across the road from the hotel. Police Constable Talbot was fetched and arrived to see not only Nora, but that of George. He was not far away ‘a double barrelled gun was between his knees, and the front part of his head was missing’.

The gun belonged to the landlord, and hadn’t been used in several months. The landlord confirmed that he had no cartridges in the house for it, but five unspent cartridges were found on the deceased. This was perhaps not unreasonable, given his profession.

The inquest revealed that this sad event had come about because of a love triangle, and Nora had been unable to choose between two suitors. Something which is also relevant to this story is that Nora Plumb had a daughter. None of those quizzed at the inquest could say how old she was, other than they estimated around three years of age. This seems awfully vague given that Nora had lived with this family since leaving school, but nevertheless, they claimed to not know much about her child. It does not state, either, whether the child lived with Nora at the hotel, or with another family member.

On searching Nora’s room, a letter was found. It had an Islington address, but was undated. It read,

“I want to thank you for a nice time. I did not half enjoy myself with Rosie after tea. I don’t think I wanted to come away really. Rosie is not half a knowing kiddie, isn’t she? She knows her daddy now, doesn’t she? I shall certainly come to see her as often as I can and nothing will stop me, not even a dozen Georges.

What I want to know is how are we going to work it on Wednesday and Sunday, when I am down there, because I don’t want a row with anybody, but if he is going about carrying a gun I can just as easy carry a razor. He is not going to interfere with me seeing you and Rosie together…

I wish you would hurry up and do something one way or another. Surely you know I would not treat you as you have heard. Once I am settled down you would alter my ways and make me a different fellow altogether like you did at the Bull. Look how you altered my ways while I was there. It is only since I have been away from your sensible ways and doings that I have got so ‘don’t-carefied’. All my love, Alf.”

Alfred Hughes had once also worked for the Richardson’s at The Bull. Mrs Richardson said that she knew they had been on friendly terms, but did not believe they had been intimate. That said, she also admitted that she knew Alf had paid support to Nora for the child. I suspect this wasn’t so much a case of supreme naivety, but more that she didn’t want to seem complicit in whatever had gone on under her roof.

Alf, now working in London, lived with his family at the White Horse in nearby Hundon. On the day in question he stated that he’d heard that she was going to choose George and becoming jealous, had travelled to Cavendish to find out if it were true. He said he had seen George at the Bull that day, but had not spoken to him. It transpired that Nora had been seeing both men on a weekly basis in the proceeding few months, but had not come to any decision as to who she would choose to marry.

Everyone that was questioned at the inquest had stated that George was a quiet man and not quick to temper, but Nora had confided to Alf that George had threatened her. Alf stated that she told him, ‘he would shoot herself and him, or her and me’ (meaning Alf). I think it’s well known these days, that even the quietest of men in public can be quite different behind closed doors, and her experience of him and hesitance to commit herself to him may have illustrated that he was like this.

George, meanwhile, ended up choosing the former of those threats he made to Nora. It was determined after the bodies were examined, that Nora had been shot in the face at a little distance and George’s wound was self-inflicted.

Both men were impatient for an answer from Nora, as evidenced in Alf’s letter, and testimony about George’s situation that came out at the inquest. George was keen to get married quickly and had told his employer that he would be married and settled as soon as possible. He job perhaps depended on it, as it came with a house which would have been unsuitable for a single man.

After the judges summing up, it took only a quarter of an hour for the jury to decide that this was a case of murder and suicide. A few minutes after the verdict, a coffin was brought to the outhouse at The Bull where the bodies had been placed. The coffin carried the inscription ‘George Newton Morley, died Sept 5th 1929, aged 37 years’. Half an hour later the coffin containing the deceased was conveyed to Cavendish cemetery. The only mourners were Morley’s two brothers, a Mr Deasley, and a Mr Long, who had served with George during the war in France. There was no burial service, but some psalms were read at the graveside.

The following Monday, Nora Plumb would be buried in Pentlow. In contrast there were many present for Nora’s funeral, including the police Inspectors who attended the crime scene. Among the wreaths were several from Alf’s family and one with the note ‘In deepest sympathy, from Rosie and Dad at Hundon’.

I can find no word as to what happened to her daughter, Rosie. It is my hope she grew up with family and wasn’t haunted by what happened to her mother. It is only my personal thoughts, but I feel so sorry for Nora and her predicament. Neither chap seemed like they would have been worth her love. George, who seemed impatient to wed and perhaps wasn’t as nice behind closed doors as he was in public. It is not unreasonable to suggest he may also have had some unresolved issues following whatever horrors he witnessed on the Western Front a decade or so before. Or Alf, who didn’t seem inclined to ‘change his ways’ off his own back and had presumably not wanted to wed her before getting her pregnant, despite being willing to acknowledge the child as his. The line in his letter that states ‘Surely you know I would not treat you as you have heard’ makes me wonder what it was she did hear. As a single mother in service her options were not great and she perhaps would have found it hard to find a man willing to take on another man’s child in an age when society had so many moral rules to follow.

It is a sorrowful tale and one that is too often repeated. If you should visit Pentlow or Cavendish, spare a moment of thought to this awful night in 1929.

There are undoubtedly more stories to tell from this quiet corner of Essex, but now I will move on to another village and see who I meet there….