Earlier this year during early summer I spent the afternoon in Abbotsbury, Dorset. It’s got to be one of the most picture perfect villages along the Jurassic Coast… and that’s saying something!

While the village seems quite small, there’s actually enough to occupy you for a whole day here. I parked at the Swannery car park, where there are also toilets and a café. Join me on my exploration of this historic settlement.

-

I couldn’t have found a more unique place to start this visit. The Swannery is the world’s only managed colony of nesting Mute Swans. More than 600 of these beautiful birds call this place home, and human visitors are welcomed between March and November.

Abbotsbury, as you may have deduced from the name, was once the site of the Benedictine Monastery of St Peter. It was founded in the 11th century and although it succumbed to the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538, its presence still echoes all around the surrounding area. Monasteries were expected to be largely self-sufficient and most had farms and fish-ponds to sustain them. The Monastery here also had The Swannery.

The Fleet Lagoon was a perfect habitat for them and the monks began farming them, with the earliest record of swan keeping here dating to 1393. Thankfully today, swan is off the menu, but the flock remains under the care of the same family that bought the Abbey and its lands after the Dissolution.

From the Swannery I decided to walk up to the village and a quick glance at the map made it immediately clear how much of this place is still amongst the bones of the old monastery. Every other building here is listed by English Heritage, so if you love heritage, this is a must visit.

The most noticeable structure has got to be the massive abbey barn. It dates to the 14th century and gives some clue as to how much the monastery complex must have dominated the landscape here. Half of it was de-roofed in the mid-17th century, but the structure is still impressive. It is now Grade I listed and a Scheduled Ancient Monument. If you walk to the end of the roofless section and peer through the doorway, you can see the Abbey dovecote. In fact, walk anywhere around here you will see remnants of the abbey farm complex. The diary, the fishponds, the mill… I would have loved to see this place alive back in the days before the Dissolution!

I walked from the abbey barn toward the church of St Nicholas, passing by a beautiful ‘Pick Your Own Flowers’ plot and stopping to look at some of the abbey ruins.

Abbey House is a former farmhouse, fashioned out of the ruined sections of the old monastery. As you approach the parish church you notice the remains of the old abbey church. Not much survives, but what does helps to illustrate the layout of the site. The day I visited it was a typical English mix of rain showers and sunshine. There was something about the landscape dripping with rain after the shower that made the place feel more alive. You could hear it all around and it offered a sense of movement to the worn stones and ruined masonry all around.

Once in the parish churchyard there are a couple of things to look out for. First, close by the south side of the church, are the remains of a 15th century churchyard cross. I say remains; it’s a stone base, but if you’re into wayside crosses and the like, I’m sure you can imagine!

Secondly, as I frequently draw your attention to in these rambles, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstones. Just one here, for Ordinary Seaman Sydney George Towills.

Sydney was born in Soho, London on 14th May 1900, before moving to West Street in Abbotsbury with his parents. After leaving school he worked as a farm labourer. With the First World War well under way, on his 18th birthday as a brown haired, blue eyed healthy teenager, he joined the Royal Navy, signing up for 12 years’ service. In a cruel twist of fate, he would never go on to complete his training on board HMS Powerful. Just seven weeks later, on 2nd July 1918, Sydney died ‘from disease’ at the Royal Naval Hospital, Plymouth. The disease was empyema. This was possibly a result of contracting pneumonia. Empyema is when pus collects in the pleural space, which is between the lung and the inner surface of the chest cavity. In pneumonia the bacterial infection forms in the lung and the pus can be coughed out, but when it develops into empyema in the pleural space it cannot, and would need to be extracted surgically. There are some things I learn while researching these graves, that I could really live with not knowing. Anything to do with pus is a good example. Nevertheless, it is important in telling his story.

Sydney was buried here in St Nicholas’ churchyard and nearby is a headstone to his parents. His father died a year later and his mother in 1928.

The church of St Nicholas dates to the 14th century, although like many churches has additions and alterations from subsequent centuries. I was lucky enough to pick up a couple of books from the book sale shelf, so it’s always worth having a look inside if that’s your persuasion. A book about maritime memorials and a book of Dorchester’s War Memorial were added to my bookshelves for a few pounds.

The church was the scene of some conflict in the seventeenth century. Colonel Strangways, the principle local land-owner, was holding the village and church in the name of the Crown during the Civil War. He was here confronted by Parliamentarian forces under Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper in 1644, and the beautiful early Jacobean pulpit was damaged by musket shot. Two holes remain in the woodwork as a reminder of these troubled times. His house nearby was the scene of a six hour skirmish as Parliamentarian forces tried to force the Royalist garrison from the village. The building was set alight and the Royalists managed to escape. Once the burning building was vacated, a number of the Parliamentarian troops went in, despite the flames, to plunder the home. Despite warnings that a powder keg was still in the property, they didn’t leave and between 50 and 60 of them were killed when it exploded, destroying the building completely. Unfortunately, the loss of this building also meant the loss of all the early records for the abbey buildings, so there are substantial gaps in our knowledge to this day.

Taking the footpath out of the graveyard and toward the village centre I came to the Ilchester Arms. This historic inn has been the centre of village life for centuries, and like many coastal settlements, also the centre of it’s smuggling activities.

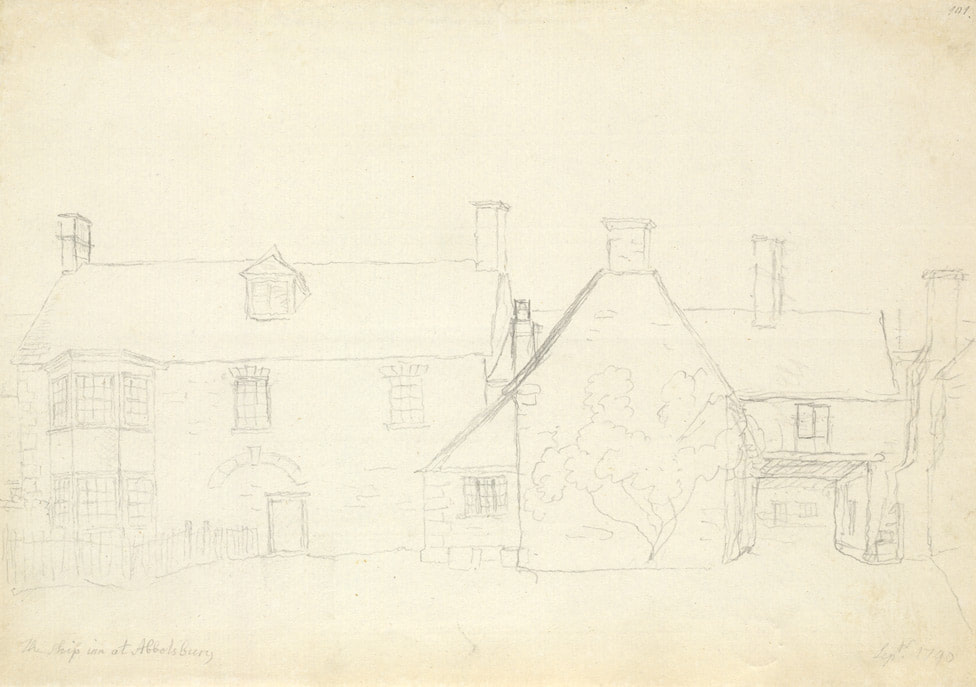

The Ilchester Arms was once known as the Ship Inn. The drawing held by the British Museum shows the inn from the back, and its features are still recognizable. The inn was mentioned in the trial of Elizabeth Canning. Her story became one of the most sensational mysteries of 18th century London. Elizabeth was an 18 year old maid servant to a house in the City of London. On the 1st January 1753 she disappeared. No sign of her was found until the evening of 29th January. She reappeared at her mother’s house in a deplorable state. She was injured and claimed to have lived on bread and water for the month while confined to a loft by her kidnappers. She accused a women and her household some ten miles distant of the crime, though the loft belonging to the woman did not match the description provided by Elizabeth. Two women at the house were arrested and put on trial. One of the women, Mary Squires, was said to be a gypsy and this prejudice went some way to convincing the public of her guilt. Feelings ran high on both sides of the case and when the women were found guilty; it was the trial judge Sir Crisp Gascoyne who decided to re-investigate it himself. You see, Mary Squires and her family had claimed to be in Abbotsbury at the time of the alleged kidnapping. In Abbotsbury she had witnesses. Many reputable characters from the village were willing to swear to the fact that Mary had been in at the Ship Inn over New Year, so couldn’t possibly have been involved. Mary had been sentenced to death at the first trial, but after Gascoyne’s successful investigation, she was pardoned in the following May. Meanwhile, Elizabeth Canning would go on to be arrested for perjury and was sentenced to transportation for seven years. She was placed on a convict ship in August 1754, landing at Wethersfield, Connecticut. She would settle there, raising a family and dying in June 1773. He real cause of her disappearance never came to light and is still a mystery to this day. Some suggest she may have willfully disappeared to deal with an unwanted pregnancy or deliver a baby, and only came up with the kidnapping story to cover her absence. We will never know.

This historic inn is also home to several ghosts, including a spectral dog and a man said to be a coin collector. Apparently he jangles his way through the corridors! As Abbotbury was a Royalist village during the Civil War, there is also said to be the ghost of a Cavalier, perhaps killed when the Parliamentarians attacked in 1644.

From the Ilchester Arm I crossed the road to take Back Street, until reaching Blind Lane on the left-hand side. Sitting on the corner of Blind Lane is a tiny 18th century cottage, known as the Basket Factory. This cottage is now Grade II listed, but in the 1920s it was a workshop to a local thatcher. Here he would make hazel spars (lengths of split hazel, used to hold thatch in place) and baskets. These were good winter tasks, when it wasn’t possible to do thatching.

Now came to a little walk out into the countryside. Blind Lane leads up on to the Dorset Ridgeway. Following it west brought me to Abbotsbury’s Iron Age Hill Fort, sometimes called Abbotsbury Castle. It was originally occupied by the Celtic Durotiges tribe, but they were forced to abandon it in AD 43 when the second Augustinian legion of Vespasian arrived as part of the Roman invasion. The Romans don’t appear to have settled here, and so it has remained an imposing but unused feature in the Dorset landscape for 2000 years.

Continuing west a little until the footpath crosses the B3157 I took a footpath to the left and headed toward the coastline.

Looking west here, marked on old maps, is the intriguingly named Labour in Vain Farm. Local legend says that it acquired this unusual name back when this land was farmed by the Abbey. One year, sometime in the middle ages, there was a particularly poor harvest and the land became known as Labour in Vain.

If you were to continue west from here you would find yourself in Bexington, by way of Swyre Lane. It was here in 1737 that 3/4 ton of tea was found under hedges, along with brandy, rum, silk, cotton, and handkerchiefs. This discovery led to the Ship Inn, now known as the Illchester Arms, to be found to be the local smuggling HQ.

I took a gap in the hedge to the left, taking the footpath through the field that skirts East Bexington Farm and which ended up at the beach.

Once on the beach looking west you will spot the old coastguard station. Originally built in 1823 as eight coastguard cottages, they are now converted to four private homes and holiday cottages. They were sold in 1924, presumably after the coastguard station closed. In the latter 1920s one was occupied by controversial author Middleton Murry, acquaintance of Thomas Hardy, who is also known to have visited here. Middleton Murry was a prolific writer. He was medically unfit to serve during the First World War and by the time of the second was a pacifist who set up a commune run by conscientious objectors somewhere in Suffolk. He was an anti-feminist who was married four times, and at times a Marxist and ‘Christian Intellectual’.

I don’t think we’d have got on. So, moving on….

I headed back toward the village along the beach. A little way along there is a footpath off the beach to the site of Abbotsbury Castle. Much like the Hill Fort is referred to as Abbotsbury Castle, and is not a castle, this site is also known as Abbotsbury Castle, but was not a castle. Instead it was a beautiful country mansion, built by the Strangeways family in 1756. This was also when they started work on the subtropical gardens, which do survive and can be visited. The house suffered a devastating fire in 1913 and was completely demolished in 1934. Nothing remains to be seen today, so I didn’t venture up to the site. as another rain burst was threatening.

I walked along the beach, passing by the footpath I needed to get back to the car park in favour of ploughing on towards some WW2 relics.Here I could see on the Google Earth a double row of anti-tank blocks. Also here, depending on the favour of the sands, a couple of pillboxes and machine gun posts. These come and go under the moving dunes, but it was worth the extra walk.

Back up to the footpath heading inland and my final stop at St Catherine’s chapel. St Catherine’s chapel was built around the same time as the other monastery farm buildings in the village, around the 14th century. It was used by the monks here for retreat and private prayer. It is likely that the chapel’s position high up on the ridge allowed it to be used as a seamark after the Dissolution of the Monasteries and ensured its preservation when the rest of the abbey complex was demolished.

Nowadays a dedication to St Catherine is rare, but during the middle ages her cult was very popular. Catherine of Alexandria lived during the reign of Emperor Maximian (286 – 305) and she became a Christian as a young teenager. When the Emperor started to persecute the Christians she confronted him, engaging in lengthy debates with his Pagan philosophers. Tired of her influence he threw her in prison and subjected her to torture. It is said that around 200 people visited her in prison, including the Emperor’s wife, and all left her company having been converted to Christianity by her words. All of these converts were martyred afterwards. The Emperor having failed to undermine her faith, finally condemned her to death on a spiked breaking wheel. It is said that the wheel shattered at her touch and she was instead beheaded. This instrument and her martyrdom are today represented by the Catherine Wheel we find at firework displays, named after her horrific torture at just 18 years old.

Catherine became the patron saint of virgins and unwed women. Local spinsters would come and make a wish in her chapel in the hopes of finding a good husband. Some still do.

I made my way back down the steep hill, passing by a Type 26 pillbox and followed the footpath back to the Swannery car park. It was a wonderful circular walk and had some of the loveliest views….

Until next time, happy adventures eveeryone!